All Along the Western Headworks Canal

Whenever I played in our backyard's sandbox as a young child, I loved a particular engineering task. I would dig a massive hole, fill that hole with water from a hose, and then build a system of channels to move that water to another section of the sandbox. This is something humans do and we have been doing it for awhile. Whether it is the qanāts of ancient Iran, upstate New York's Erie Canal, or the titular Panama Canal, humans have worked to design and construct canal systems throughout our civilization's planetary history. Sometimes, we use these canals to make the region more navigable. Other times, we might use them to secure water supply for consumption by nearby human settlements. But for the Western Headworks Canal, since 1904, this canal system has been diverting water from the Bow River for the purpose of irrigation (though consumption does matter as well). The semi-arid region that the Western Irrigation District manages irrigation for requires dependable water sources for agriculture. The canal itself has existed for over a century, with upgrades and repairs scattered throughout its history, but this canal is outside the view of most Calgarians, though not likely for the farmers who depend on it. A dependency that will only deepen as the climate crisis amplifies drought in the region.

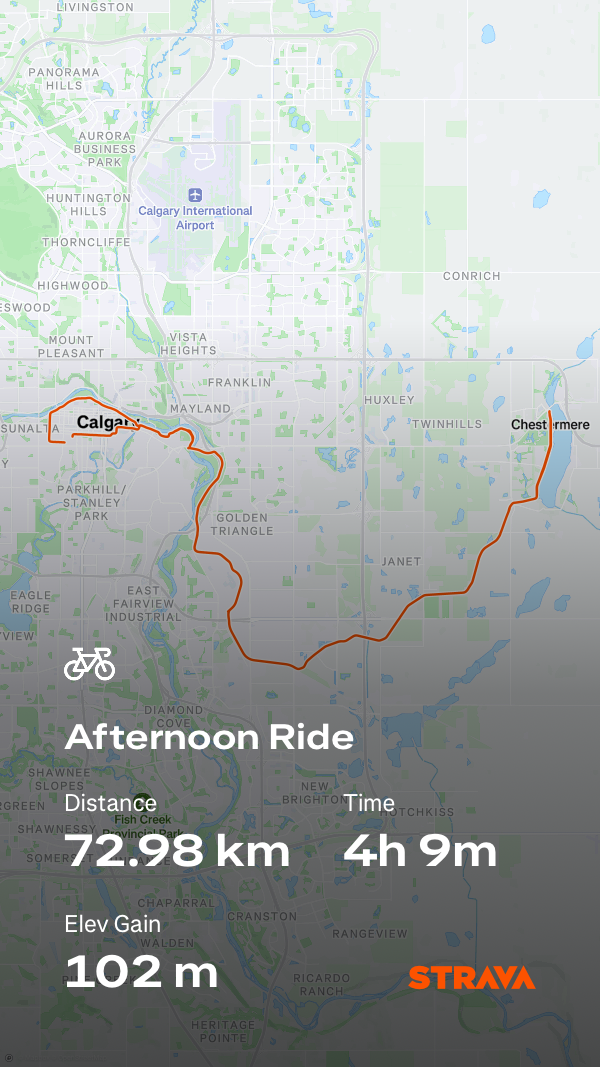

The Western Headworks Canal Pathway, opened in 1991, runs along this canal for its entirety; from the headgates near Harvie Passage, through much of our city's industrial heartland, into the rural outskirts to the city's east, and to Chestermere Reservoir (more commonly known as Chestermere Lake). Alida and I decided to take our bikes along this pathway to explore this underappreciated infrastructure.

Starting at 8 AM on August 17th, we left the highrise-dominated Beltline along the 12th Ave Bike Lane, connecting with the Bow River Pathway, until we diverted from the serene recreational pathways near Pearce Estate Park/Harvie Passage down an odd path near the partial cloverleaf interchange connecting Blackfoot Trail and Deerfoot Trail. This is where the canal's pathway earnestly started. The fast-moving glacial waters of the Bow is replaced by a much slower, and by extension, murkier waterway. The canal's water is populated by waterfowl of all sorts, from common mergansers to mallards, but it is the pondweed that stands out. This aquatic plant is a feast for waterfowl and it is plentiful through the entire canal system, but it does reduce water flow to the annoyance of many. It is prolific here due to pondweed's resilience in the face of eutrophication: the process where nutrients accumulate in water (often from industrial or agricultural runoff), causing a growth in organisms, that eventually deplete the oxygen in the water.

As we proceeded through this part of the pathway, it became quite apparent that this trail, whilst nestled along the highway, is fairly isolated. The exception to this is exemplified by two pathway users: (1) those who use it for recreational purposes (cyclists like us for example) and (2) those who use it for housing purposes (namely the unhoused Calgarians who have set-up encampments along the canal). From shallow underpasses to forested groves, tents act as temporary home to folks who have no other option left. Meanwhile, this canal runs through constituencies that were won by the United Conservative Party: a party that exemplifies the art of punching-down on the worst off within our society. But I digress, because as we headed south, the pathway's surroundings change (as they did again and again).

As we passed abandoned shopping carts, idling dog walkers, and rail lines, Calgary's industrial parkland revealed itself. The facilities were often non-descript and enclosed behind wire fencing, but careful observation and attention to online maps revealed many points of interest. There were a few examples that stood out. For starters, initially marked by dirty white powder mounts and a couple white blooms billowing from the facility, there was a gypsum recycling plant that turns construction materials, like gypsum board (also known as drywall), back into new gypsum products (removing foreign contaminants and paper lining in the process). Further still, there was a mass graveyard of automobiles or car-casses (pause for laughter), that formed the basis of an auto parts shop. Other industrial yards were full of steel rebar and freighter trucks.

As the pathway started the turn north (and the smell of the landfill slowly intensified), the industrial parkland shifted again, with mausoleum-like colossal warehouses (including Amazon) and oil terminals near the canal (though similarly surrounded by fenced perimeters). It is easy to focus on the large built-structures along the path, but I do want to mention that while these act as reminders of global capitalism, so to does the noxious invasive plants and fragments of plastic waste. Musk thistle might be beautiful, but it competes with local biodiversity. Potato chip bags might have contained salted and sliced spuds at one point, but it pollutes our local waterways. Both examples are, to use a neoliberal euphemism, negative externalities. They are the allegedly "unintended" negative costs that economic activity shoves onto uninvolved third-parties. Third-parties like, I don't know, the fucking planet.

As the density of fenced industrial facilities and warehouses thinned, the landscape became more verdant. The open blue skies and rain-drenched prairies defined the horizon now. So far, since the headgates, the canal has existed as a long and convoluted artificial channel (with slopes on its edges) through an industrial park, but out here in the countryside, the canal's infrastructure changes. As the elevation changes going east, the canal needs to be engineered to adapt to such through weirs (also known as drop structures) to manage the water's flow. These allow the water level to alter in a controlled and measured way that mitigates the possibility of flooding. Additionally, to start diverting water for irrigation purposes, a lock system allows the right amount of water to be diverted for farmers to use. Eventually, after harvest (around October), the headgates will close and reduce water flow. This has the consequence, by the nature of the canal's intimate connection with the Bow River's fresh water, of leaving freshwater fish to perish as the canal's remaining water freezes going into winter (known as entrainment). There a lot of good folks who spend brisk autumn days rescuing trout from these irrigation canals, but ultimately, there needs to be infrastructural upgrades to account for freshwater fish populations. Again, there is a negative externality at work here and the government is allowing the environmental costs to be overlooked in the interest of agribusiness.

Beyond the canal, in the countryside we started to see sloughs full of avian activity, towering rows of transmission lines, horses (humanity's actual best friend - sorry doggo), and the fields full of crops. Eventually, the new suburban developments of Chestermere, the eastern bedroom community, came to view. As we approached, the activity along this trail, as one could expect, sprung to life - especially as the lake presented itself. Dogs crashed into the water and families spent quality time walking along its shores. The Chestermere Reservoir is a site for recreation, much like Calgary's Glenmore Reservoir. Strikingly though, on our way along West Chestermere Drive, I noticed that this wonderful lake was dominated by lakeside residential properties. As is often the case, the enjoyment of this land and water is semi-privatized, and in doing so, it is made less accessible to everyone else in the neighbourhood. The real estate agents, through their signage, indicate their understanding of this exclusivity. One sign suggested that a prospective buyer could build their "dream home" on a vacant plot of land full. The exception to this private leisure comes much further north (ironically past a private member's golf club): Chestermere's Anniversary Park. This park has a great sandy beach for the public to enjoy, public restrooms, and a lovely plaza with seating to sunbathe, read a book, or in our case, rest our weary bodies while we had a much needed break. After a brief respite, we decided to turn back and head the exact route we took to get there. It was busier along the pathway with more cyclists and grasshoppers than the hours prior.