Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve

I have always been a man of the prairies. For as long as I've had the blessing of being on these lands, I have called the great plains of North America my home. Under these open blue skies, I find peace. But as someone who has lived my life without an automobile, I have ventured less often than some to the higher reaches found west of Calgary. Whenever I am lucky enough to enter these regions, they inspire an earnest sense of awe. Greater Good Magazine defines "awe" as the "feeling we get in the presence of something vast that challenges our understanding of the world". It is an animistic feeling; something innate and beyond measurement. In a digital era defined by code and calculation, to embracing this feeling is more counter-cultural than ever. Visiting places like this remind me that we can resist this decadent culture and remember that our planet's majesty always takes priority.

On the 24th of August 2025, Alexis and I drove out to Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve to join the Alberta Wilderness Association for a guided event through the land to discuss this region's unique whitebark pine ecosystems, but also to freely explore a genuinely unique part of our province. But let's start with the trees, because they indicate something about the rare beauty of this place.

Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis) is an endangered species of conifer that is native to mountainous regions of western North America. Unique local habitats form within whitebark pine forests - making these pine trees a keystone species, not dissimilar to wolves or sea otters, in their respective homes. Whitebark pine are often found at very high elevations, higher than many other trees can tolerate, meaning they exist very close to, or on, a mountain's tree line. Compared to relatively fast-growing trees, like many willows and poplars, the whitebark pine take multiple decades to reach the point where they can form cones (and this slow growth is paired with long life - often living for over 500 years). Their cones happen to be very desirable by another local species. The Clark's Nutcracker, a less well-know member of the corvid family (and unfortunate namesake to the Lewis and Clark Expedition), lives in a mutualist relationship with these pine trees. As much of a bounty as the cones themselves might be for the Clark's Nutcracker, the whitebark pine trees depend on these birds entirely to assist in dispersing their seeds for regeneration. The avian and arboreal are united in an ecological dance of sorts. Their futures are intertwined. In fact, these creatures are so intertwined that the biology of the Clark's Nutcracker has evolved to include a "pouch in their throat where they can store up to 150 whitebark seeds." These seeds will be stored in clusters of caches - which will hopefully turn into whitebark pine saplings.

Unfortunately, a combination of challenges is putting the ecological security of these high-altitude forests at risk. An introduced fungal disease called white pine blister rust is reeking havoc on the trees themselves. Starting in the needles, which often become a sickly brown, this cankerous disease spreads and deforms the tree, resulting in the whitebark pine not receiving adequate nutrients. Then there are the Mountain Pine Beetles. Whilst many trees further to the west have adapted to them over time, forests on our side of the Rockies are having challenges. These challenges are caused by many factors, including forest mismanagement, but climate change has a major role here. Normally, brutal cold snaps can keep their population and range in check, but with more mild winters, they are able to maintain large populations and spread into forests that are less adapted, like whitebark pine ecosystems. Furthermore, if you've paid any attention to the discussions regarding wildfires over the years, you will likely know that decades of fire suppression is disrupting North American forests too. Wildfires play an ecological role in purging a forest's underbrush (sometimes even leaving large trees intact). As a result, well-meaning fire suppression efforts have resulted in a build-up of "fuel". This can include dead trees and leaf matter, but also the shade-loving plants. This leftover fuel makes future fires more vicious, while also creating another issue. Shade-loving plants - without wildfires to keep them in check - grow abundant, resulting in fiercer ecological competition. Whitebark pine trees, already under stress, are put under even greater pressure.

With these threats known, there are good folks who have dedicated themselves to stewardship of these forests (though perhaps land guardians is a more apt title). Our guide worked with nurseries (as far as New Zealand) to raise more-resilient saplings and with other tree-planters to set these saplings up for success here at Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve. But folks can only do so much, especially when the conservationists' job is made more difficult by the climate crisis at large. Fundamentally, any life endemic to a specific environmental condition - in this case the limited range amongst the Rocky Mountains' treeline - is at risk. The rapid increase of global temperatures undermines the ability of these trees to prosper. The added ecological challenges posed by the likes of mountain pine beetles and blister rust are further threat multipliers.

How is a pine tree that lives over half a millennia expected to respond to the radical ecological transformations ushered in by apes with assembly lines and airliners? These whitebark pine trees are running into an issue of time (and so are we). There is simply not enough of it to adapt to the pace of global transformation. Speculative fiction often depicts a future where the Martian volcanic plateau of Tharis is a site for terraforming (and naturally - colonization), but we are dangerously conducting a grand planetary reshuffling on our own sacred planet. High-altitude environments, like Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve, face the consequences of humanity's reckless behavior through the climate crisis. This will get worse and have dramatic implications for species dependent on these habitats. Keystone species like whitebark pine will be affected, but so will this unique ecosystem's smaller - but no less impressive - inhabitants.

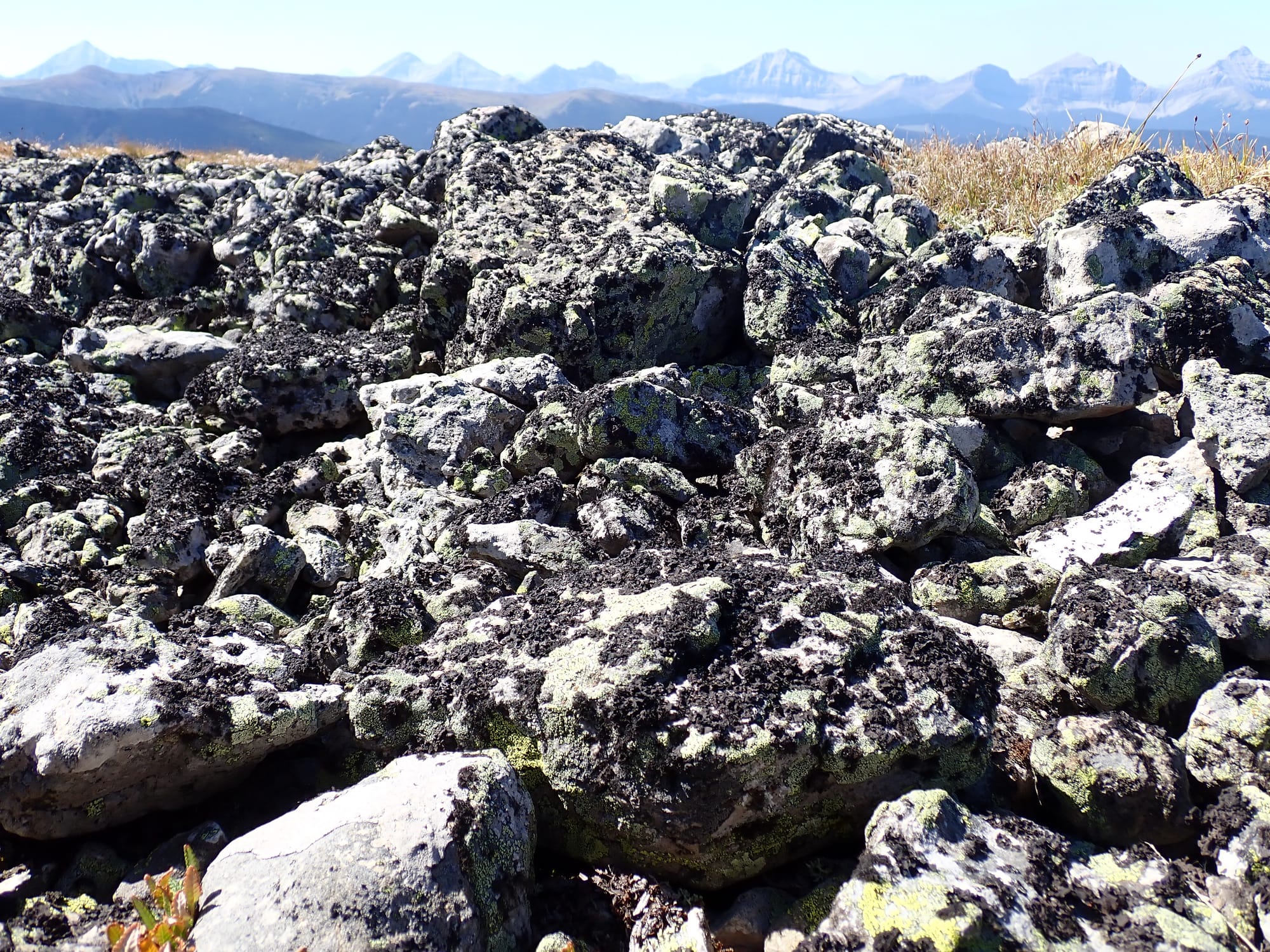

As there is much beauty to behold above, like the Golden Eagle and American Goshawk soaring across the cloudless sky, there is much to appreciate below the tree line too. Even inattentive eyes will be hard-pressed to miss the world of gargantuan mushrooms (the size of dinner plates!), bright alpine wildflowers, and vibrant lichen (which coat every rocky and barky surface). On a personal level, I have always found lichen to be truly fascinating. Lichen has challenged the categorization of life greatly, because as a fungus-algae symbiosis, it refuses to submit to simplified Linnaean taxonomy. Further still, it makes its home in even the most extreme climates that still boggle human understanding. On our trip, there was plenty of lichen to appreciate, but I will mention a few of the highlights. Amongst the conifers, you can see bright yellow-green coral-structures hanging on the branches. This is Wolf Lichen (Letharia vulpina) and it is a form of fruticose lichen (which are shrubby). I also found Whiteworm Lichen (Thamnolia vermicularis), a white fruticose lichen, snaking along the plateau's surface. But the rocks scattered around this plateau is where I found the most varied species of lichen. On these rocks, I found yellow-green of Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum), orange-red Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Rusavskia elegans), and some sort of black rock tripe lichen that I have yet to identify. Rocks make excellent homes for lichen for good reason, as explained in this wonderful video.

A highlight of this plateau's botanical life was the sporadic Moss Campion (Silene acaulis). Contrary to the name, it is not really a moss, but rather comes from the carnation family. It looks like a cushion of green moss and often has small purple flowers (though it felt denser than I imagined it would feel). It has a circumpolar distribution and live in all sorts of extreme cold environments. While it might be stunning to think of how slowly whitebark pine trees grow, moss campion are similarly slow and have their flowers often emerge ten years into their life. Many other wildflowers were found on this plateau too. Both Cut-leaf Fleabane (Erigeron compositus) and Alpine Yellow Fleabane (Erigeron aureus), members of the daisy family, were found (with the latter of the two being found in a much more limited range). Sulking closer to the ground were Hooker's Mountain-Avens (Dryas hookeriana) of the rose family that is found in western North America along the Rockies, though it is circumpolar in distribution (Iceland considers it their national flower). There were two species found from the stonecrop family: Western Roseroot (Rhodiola integrifolia) and Lanceleaf Stonecrop (Sedum lanceolatum). Now roses and daisies might be familiar to you, but stonecrops are defined by fleshy succulent that store water and enact a form of photosynthesis called crassulacean acid metabolism. This process works by allowing the plant to photosynthesize during the daytime, but keeps the stomata closed, at least until the night time. This can be advantageous in arid regions, as it reduces the plant's transpiration (to simplify, this is how water moves from plants to the atmosphere). In the nighttime, however, the stomata opens and that allows the stonecrop to acquire carbon dioxide (followed by some biochemical shenanigans that I have yet the foundational knowledge to comprehend). As an interesting note regarding crassulacean acid metabolism, there is a beloved fruit that employs this trick: the pineapple!

And with these botanical residents of the plateau comes the pollinators, because even at these heights, wildflowers are the site for this blessed ecological wonder. On some fleabane, our group found so many pollinating insects. Many of which were butterflies like Milbert's Tortoiseshell (Aglais milberti), Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius smintheus), and some variant of copper butterfly (currently waiting on verification through iNaturalist). Of course, there were bumblebees and one of the interesting ones (identified days later by an observant person who joined our group) was a cuckoo bumblebee. This bumblebee, upon investigating more online, is considered "socially parasitic." Basically a female cuckoo bumblebee covertly infiltrates an established bumble bee nest. Upon getting into the host nest, they usurp or kill off the nest's queen, then replace them (reaping all the good that comes with being a bumblebee aristocracy). It kind of reminds me of Inventing Anna (which is a movie that Taylor watched and I heard about). I guess there is also a Gossip Girl equivalent as well, but I digress. And then, there was the adorable bee fly. In general, bee flies (the family is referred to as bombyliidae) are an extremely diverse group with around 4,500 species with some being pollinators. Despite how plentiful they are, there is still much to observe and learn about their lives, as Wikipedia indicated that they are comparatively under-researched. The species I found up on Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve seems to have no common name, but its Latin name is Anastoechus barbatus. The white-grey fuzzy beast had a wonderful proboscises and was enjoying the previously-mentioned fleabane. All of this life finds a way in this high-altitude climate. But despite their resilience, climate change presents a sincere threat. How much life will be vanished from this plateau with each degree of warming?

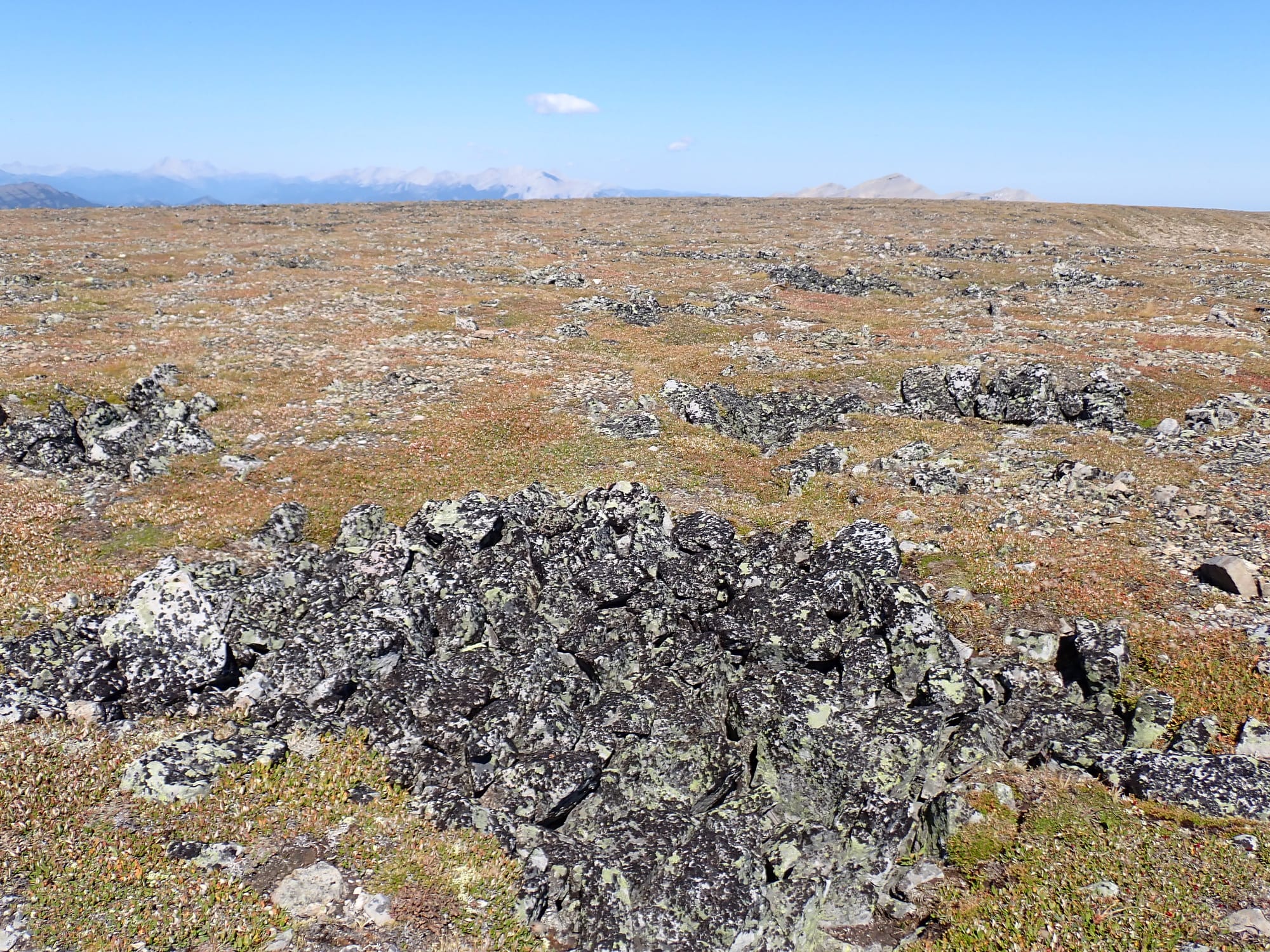

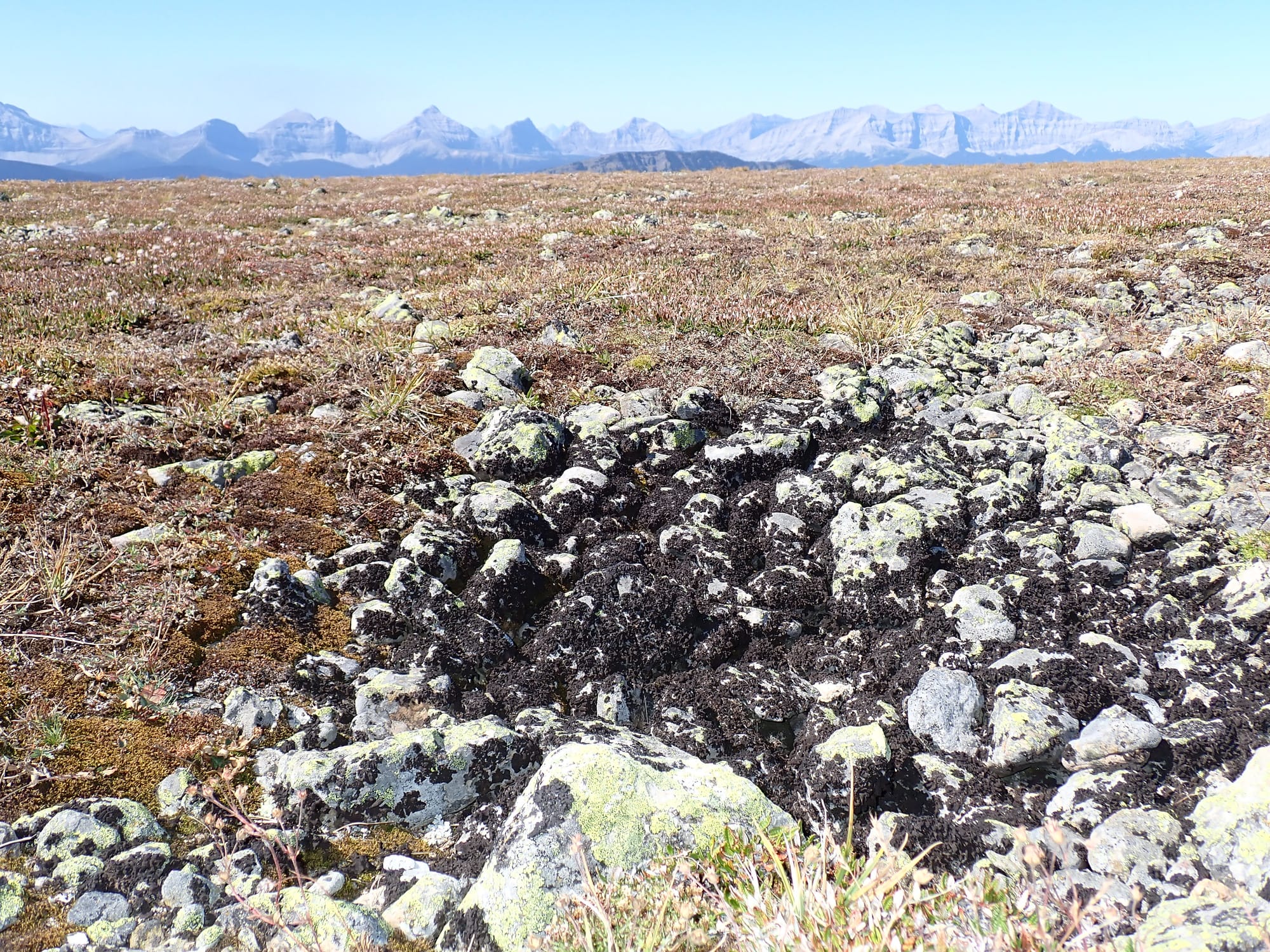

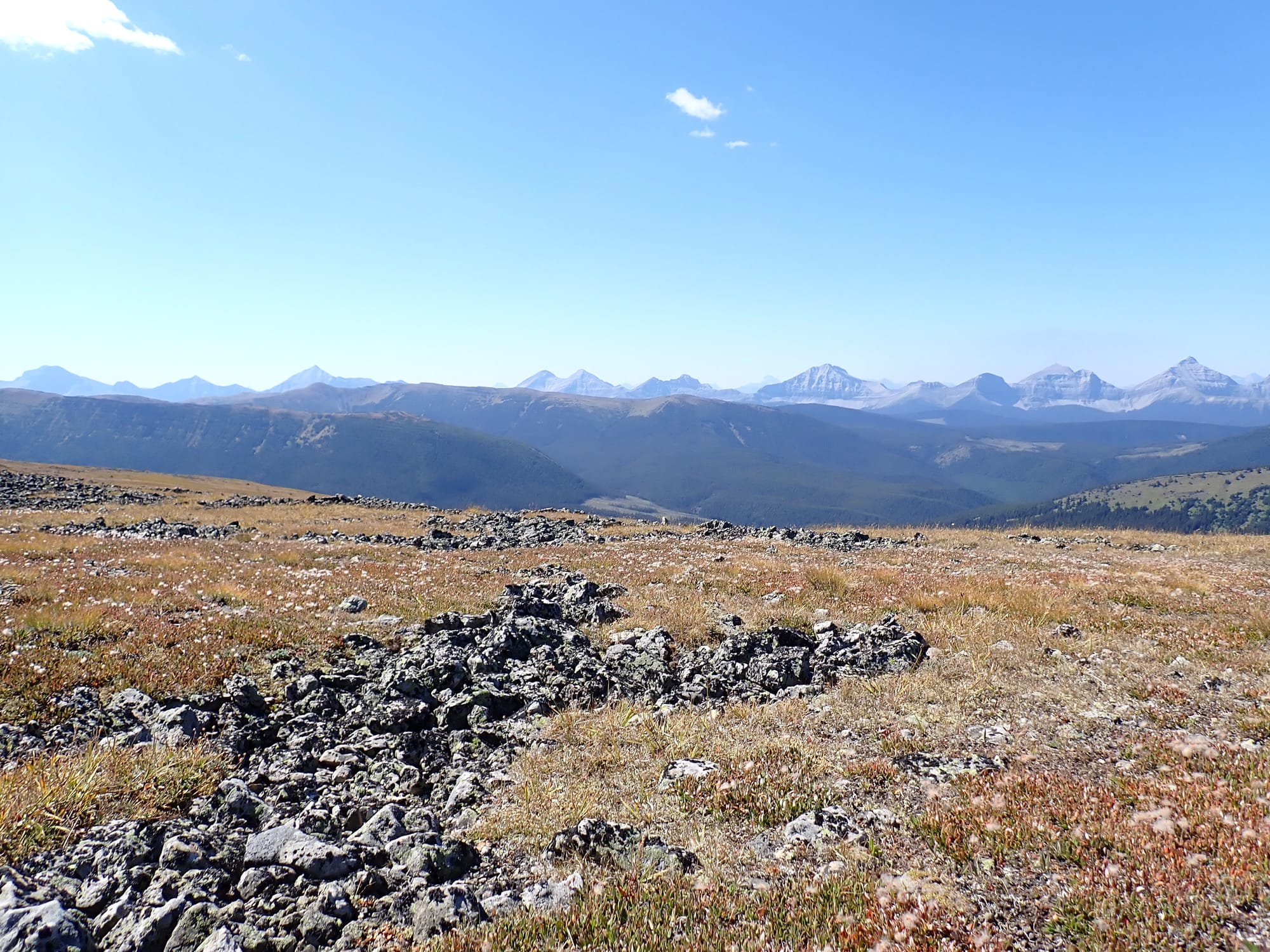

Plateau Mountain Ecological Reserve's life is certainly remarkable, but if I am being honest, the Friends of Kananaskis Country website got my attention by noting how special this land is geologically-speaking. For starters, this plateau, which is defined by its relatively high elevation and its flatness, is unglaciated. This means that during the last ice age, this land was untouched by the glaciers that dominated the rest of the region. This plateau is called a "nunantuk" and it results in a rocky/jagged surface. For this reason, the landscape looks more ancient in its own way. Then there is, like much of the Canadian tundra, a layer of permafrost just below the plateau's surface. This permafrost, and the land's freeze/thaw cycle, has resulted in a geological feature called patterned ground. This is caused by a process called frost heaving which forces stones to the surface in specific geometric shapes (like rings or polygons). Though an aerial view would be incredible in its own right, walking across this plateau does justice to this awesome feature too. As you scan the plateau, patterned ground will present itself as small batches of lichen-covered stones bursting out of the soil. Whilst I do not know, I do wonder how long it would have taken for this plateau's surface to decorated with such patterns? In any case, the patterned ground's peculiarities are matched by the oddly crisp, but sponge-like, sensation of taking each step across the land. As we departed the plateau in the mid-afternoon, we stopped to see if we could spot pikas amongst a limestone outcrop (sadly, we did not spot pikas). The limestone was beautiful in the afternoon sun and the only thing that brightened these white stones more was the contrasting multicoloured lichen on them.

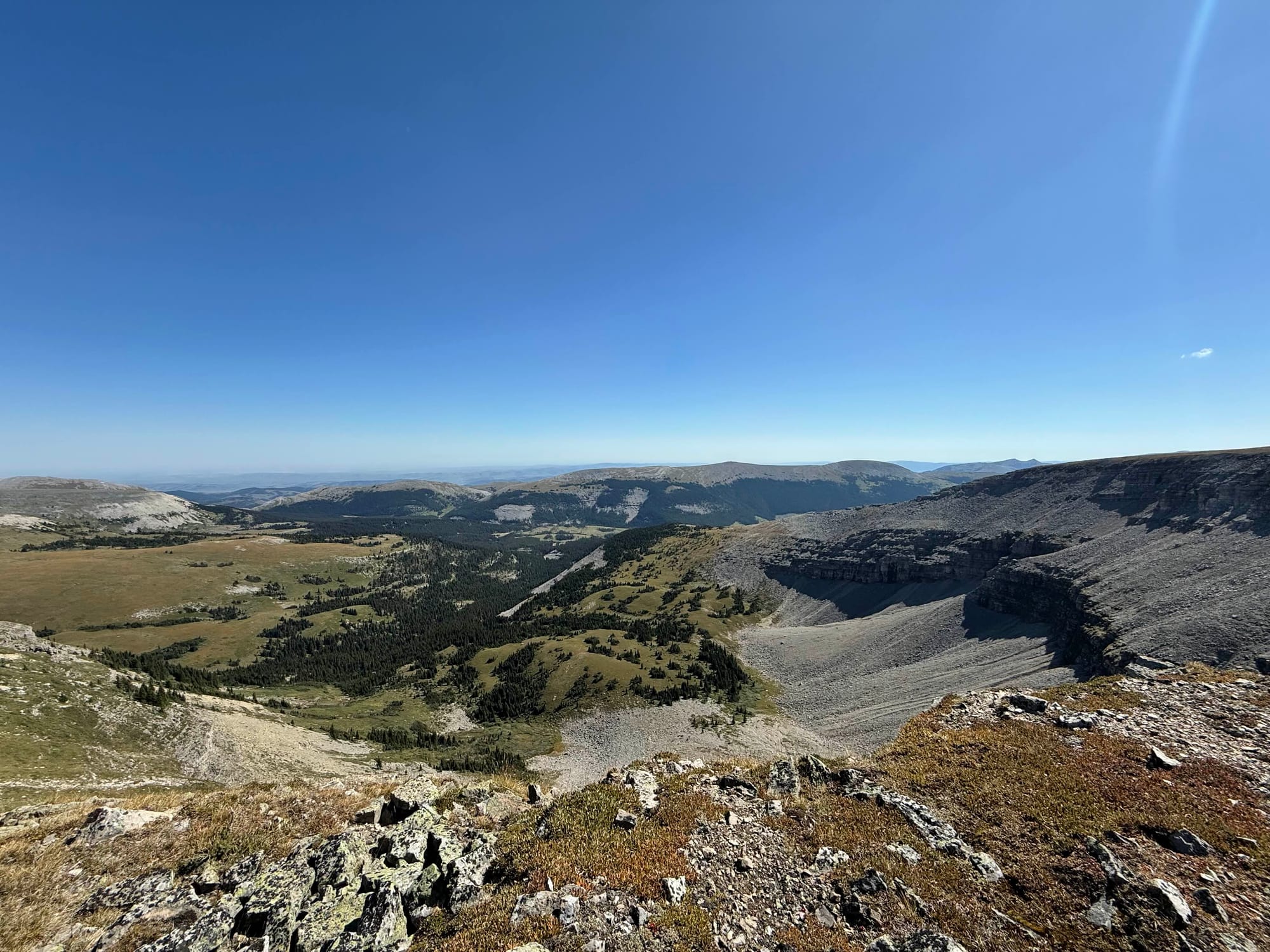

The geological elements of this land are highlights, certainly. But it is the breathtaking vistas that ignite the human soul. It is not wonder that the German Romanticist, Caspar David Friedrick, painted the towering Alps with such mystique and grandness in his 1818 Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. A perspective on mountaineering and their thirst for the summit exists today that characterizes fool-hardy adventurers (always depicted as Westerners) as attempting to dominate the mountains themselves. Though there is a degree of truth here, it uncharitable to a broader and more-humanist lens. Peoples, from across the globe and for millennia, have found awe in these high-altitude worlds. Simply put, there is something magical about the silence in a moment of enjoying lunch and taking in the expansive view. Even this 2,500 meter climb, humble in heights along the Rockies, gives pause. From the vertigo-inducing fear to the elated joy, these heights remind me that I am an animal. And animals, when under threat, fight back. The climate crisis can seem impossible to comprehend and daunting to address as an individual. I often wonder what I can offer and it feels me with a sense of dread, but nihilism is a luxury that I cannot afford. But while I do not know where to start with climate action, I will figure it out if it means that I might give this land a fighting chance.

Of Whitebark Pine

Of Lichen, Wildflowers, and Fungi

Of Stunning High-Altitude Pollinators

Of Geology and Vistas

Of Friends